Last Friday April 1, Eric Leeper Tom Coleman and I organized a conference at the Becker-Friedman Institute, "

Next Steps for the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level." Follow the link for the whole agenda, slides, and papers.

The theoretical controversies are behind us. But how do we

use the fiscal theory, to understand historical episodes, data, policy, and policy regimes? The idea of the conference was to get together and help each other to map out this the agenda. The day started with history, moved on to monetary policy, and then to international issues.

A common theme was various forms of price-related fiscal rules, fiscal analogues to the Taylor rule of monetary policy. In a simple form, suppose primary surpluses rise with the price level, as

\[ b_t = \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} \beta^j \left( s_{0,t+j} + s_1 (P_{t+j} - P^\ast) \right) \]

where \(b_t\) is the real value of debt, \(s_{0,t}\) is a sequence of primary surpluses budgeted to pay off that debt, \(P^\ast\) is a price-level target and \(P_t\) is the price level. \(b_t\) can be real or nominal debt \( b_{t}= B_{t-1}/P_t\), but I write it as real debt to emphasize the point: This equation too can determine price levels \(P_t\). If inflation rises, the government raises taxes or cuts spending to soak up extra money. If inflation declines, the government does the opposite, putting extra money and debt in the economy but in a way that does not trigger higher future surpluses, so it does push up prices.

(Note: this post has embedded figures and mathjax equations. If the last paragraph is garbled or you don't see graphs below, go

here.)

That idea surfaced in many of the papers.

The morning had several papers studying the gold standard and related historical arrangements. To a fiscal theorist the gold standard is really a fiscal commitment. No gold standard has ever backed its note issue 100%; and none has even dreamed of backing its nominal government debt 100%. If a government had that much gold, there would be no point to borrowing.

So a gold standard is a commitment to raise taxes, or to borrow against credible future taxes, to get enough gold should it ever be needed. The gold standard says, we commit to pay off this debt at one, and only one, price level. If inflation gets big, people will start to want to exchange money for gold, and we'll raise taxes. If inflation gets too low, people wills tart to exchange gold for money, and we'll print it up as needed. Usually, in the fiscal theory,

\[ \frac{B_{t-1}}{P_t} = E_t \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} \beta^j s_{t+j}\]

the expectation of future surpluses is a bit nebulous, so inflation might wander around a lot like stock prices. The gold standard is a way to commit to just the right path of surpluses that stabilize the price level.

A summary, with apologies in advance to authors whose points I missed or misunderstood:

Part I: HistoryGeorge Hall presented his work with Tom Sargent on the history of US debt limits, together with a fantastic new data set on US debt that will be very useful going forward.

|

| Price of a Chariot Horse: 100,000 Denarii |

François Velde and Christophe Chalmley took us on a lighting tour of monetary arrangements across history, prompting a thoughtful discussion on just where Fiscal theory starts to matter and where it really is not relevant. (François easily gets the prize for the best set of slides. Picking just one was hard.)

Michael Bordo and Arunima Sinha presented an analysis of suspensions of convertibility: Governments temporarily abandon the gold standard during war, then go back at parity afterward. Maybe. By going back afterward, people are willing to hold a lot of unbacked debt and currency during the war. But sometimes the fiscal resources to go back afterward are tough to get, the benefits of establishing credibility so you can borrow in the next war seem further off. When people are unsure whether the country will go back, the wartime inflation is worse, and the cost of going back on parity are heavier. They analyze France vs. UK after WWI.

Martin Kleim took us on a tour of a big inflation in a previous European currency union, the Holy Roman Empire in the early 1600s. Europe has had currency union without fiscal union for a long time, under various metallic standards and coinages. In this case small states, under fiscal pressure from the 30 years' war, started to debase small coins, leading to a large inflation. It ended with an agreement to go back to parity, with the states absorbing the losses. (In my equation, they needed a lot of surpluses to match \(P\) with \(P^\ast\)). We had an interesting discussion on just where those funds came from. Disinflation is always and everywhere a fiscal reform.

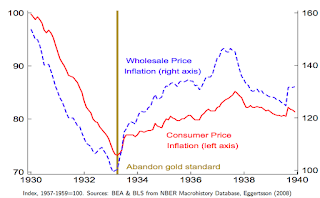

Margaret Jacobson presented her work with Eric Leeper and Bruce Preston on the end of the gold standard in the US in the 1930s. (Eric modestly stated his contribution to the paper as finding the matlab color code for gold, as shown in the graph.) Margaret and Eric interpret the fiscal statements of the Roosevelt Administration to say that they would run unbacked deficits until the price level returned to its previous level, the \(P^\ast\) in my above equation. Much discussion followed on how governments today, if they really want inflation, could achieve something similar.

Part II Monetary Policy Chris Sims took on that issue directly. If you want inflation, just running big deficits might not help. Hundreds of years in which governments built up hard-won reputations that when they borrow money, they pay it off, are hard to upend immediately. Even if you want to break that expectation -- all our governments have mixed promises of stimulus now with deficit reduction later. A devaluation would help, but we don't have a gold standard against which to devalue, and not everyone can devalue relative to each other's currency.

Chris' bottom line is a lot like Margaret and Eric's, and my fiscal Taylor rule,

Coordinating fiscal and monetary policy so that both are explicitly contingent on reaching an inflation target — not only interest rates low, but no tax increases or spending cuts until inflation rises.

But,

• This might work because it would represent such a shift in political economy that people would rethink their inflation expectations.

Chris led a long discussion including thoughts on rational expectations -- it's a stretch to impose rational expectations on policies that have never been tried before (though our history lesson reminded us just how few genuinely novel policies there are!)

Steve Williamson followed with a thoughtful model full of surprising results. The stock of money does not matter, but fed transfers to the treasury do. (I hope I got that right!)

My presentation (slides also

here on my webpage) took on the "agenda" question. The basic fiscal equation is

\[\frac{B_{t-1}}{P_t} = E_t \sum M_{t,t+j} s_{t+j} \]

For the project of matching history, data, analyzing policy and finding better regimes, I opined we have spent too much time on the \(s\) fiscal part, and not nearly enough time on the \(M\) discount rate part, or the \(B\) part, which I map to monetary policy.

I argued that in order to understand the cyclical variation of inflation -- in recessions inflation declines while \(B\) is rising and \(s\) is declining -- we need to focus on discount rate variation. More generally, changes in the value of government debt due to interest rate variation are plausibly much bigger than changes in expected surpluses. As interest rates rise, government debt will be worth a lot less, an additionan inflationary pressure that is often overlooked.

Then I presented short versions of recent papers analyzing monetary policy in the fiscal theory of the price level. Interest rate targets with no change in surpluses can determine expected inflation, but the neo-Fisherian conundrum remains.

Harald Uhlig presented a skeptical view, provoking much discussion. Some main points: large debt and deficits are not associated with inflation, and M2 demand is stable.

I found Harald's critique quite useful. Even if you don't agree with something, knowing that this is how a really sharp and well informed macroeconomist perceives the issues is a vital lesson. I answered somewhat impertinently that we addressed these issues 15 years ago: High debt comes with large expected surpluses, just as in financing a war, because governments want to borrow without creating inflation. The stability of M2 velocity does not isolate cause and effect. The chocolate/GDP ratio is stable too, but eating more chocolate will not increase GDP.

But Harald knows this, and his overall point resonates: You guys need to find something like MV=PY that easily organizes historical events. The obvious graph doesn't work. Irving Fisher came up with MV=PY, but it took Friedman and Schwartz using it to make the idea come alive. That is the purpose of the whole conference.

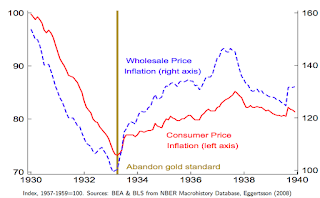

Francesco Bianchi presented his work with Leonardo Melosi on the Great Recession. New Keynesian models typically predict huge deflation at the zero bound. Why didn't this happen? They specify a model with shifting fiscal vs money dominant regimes. The standard model specifies that once we leave the zero bound we go right back to a money-dominant, Taylor-rule regime with passive fiscal policy. However, if there is a chance of going back to a fiscal-dominant regime for a while, that changes expectations of inflation at the end of the zero bound. Even small changes in those expectations have big effects on inflation during the zero bound (Shameless plug for the

New Keynesian Liquidity Trap which explains this point very simply.) So, as you see in the graph above, the "benchmark" model which includes a probability of reverting to a fiscal regime after the zero bound, produces the mild recession and disinflation we have seen, compared to the standard model prediction of a huge depression.

Fiscal policy is political of course. Campbell Leith presented, among other things, an intriguing tour of how political scientists think about political determinants of debt and deficits. My snarky quip, we learned with great precision that political scientists don't know a heck of a lot more than we do! But if so, that is also wisdom.

Part III International |

red line regime switching probability of 30%, blue line 0 % |

Alexander Kriwoluzky presented thoughts on a fiscal theory of exchange rates, applying it to the US vs. Germany, the abandonment of the gold standard and switch to floating rates in the early 1970s. An exchange rate peg means that Germany must import US fiscal policy as well, importing the deficits that support more inflation. Germany didn't want to do that. People knew that, so a shift to floating rates was in the air. Expectations of that shift can explain the interest differential and apparent failure of uncovered interest parity.

Last but certainly not least, Bartosz Maćkowiak presented a thoughtful analysis of "Monetary-Fiscal Interactions and the Euro Area’s Malaise" joint work with Marek Jarosińsky.

Echoing the fiscal Taylor rule idea running through so many talks, they propose a fiscal rule

\[ S_{n,t} = \Psi_n + \Psi_B \left( B_{n,t-1} - \sum_n \theta_n B_{n,t-1} \right) + \psi_n (Y_{n,t}-Y_n) \]

In words, each country's surplus must react to that country's debt \(B_n\), but total EU surpluses do not react to total EU debt. In this way, the EU is "Ricardian" or "fiscal passive" for each country, but it is "non-Ricardian" or "fiscal active" for the EU as a whole. In their simulations, this fiscal commitment has the same beneficial effects running through Leeper and Jabcobson, Bianchi and Melosi, Sims, and others -- but maintaining the idea that individual countries pay their debts.

A big thanks to the Harris School and the Becker-Friedman Institute who sponsored the conference.